Main author

Michael BrooksInterview with Tom Dyckhoff

Tom Dyckhoff is one of Britain’s best-known architecture and design commentators, having regularly appeared on BBC2’s ‘The Culture Show’ and recently fronted ‘The Great Interior Design Challenge’. Aside from TV, Dyckhoff has presented Radio 4’s ‘The Design Dimension’ and written extensively for The Guardian, The Times, GQ, Icon, and the Sunday Telegraph.

In ‘The Age of Spectacle’, Dyckhoff provides a thought-provoking and entertaining account of the radical transformation that the modern city has undergone over the last 50 years. He begins by describing the moment in 2012 that ‘tipped him over the edge’, on seeing China’s Gate to the East, or as it became known to the incredulous media, the ‘big pants building’.

To Dyckhoff, this was a building emblematic of the increasingly bizarre, yet strangely anonymous, architecture of the 21st century spectacle that was well-and-truly in the ascendance.

Despite its generous length, it seldom feels like the book drags and it certainly won’t alienate readers with complex theory to the extent that another recent book tackling much the same subject matter – ‘The Architecture of Neoliberalism’ – may have been guilty of.

While much of what Dyckhoff explores – the rise of gentrification, brash corporatism, the development of the city into an ‘entrepreneur’ to generate opportunities for maximising value – has been covered before by various writers (Owen Hatherley, Rowan Moore, et al), there are some sections that feel much fresher, particularly the tumultuous recent history of Covent Garden, to which many who peruse the high-end brand stores or try to elbow through the thick crowds of tourists, may know little about.

Designing Buildings Wiki chatted with Dyckhoff about the book, as well as about which UK building he would demolish if given the chance, the microhousing trend, the upcoming General Election, and more…

| Designing Buildings Wiki (DBW): Is there a city or nation that has to some extent resisted the trappings of the architectural ‘spectacle’ in favour of more well-planned, functional or communal urban design? |

Tom Dyckhoff (TD):

I don’t think everywhere has succumbed across the world. I talk about the spectacle as being a condition, it’s a culture that’s grown since the 1970s across the world and gets applied in different places in different ways.

In places where the free market has been unleashed as much as possible the condition of spectacle has flourished more. The story told by the book concentrates very heavily on the relationship between America and Britain over the last 50-60 years as one has taken over from the other as the leading world power.

In places where there is more state intervention or regulation, historically continental Europe and Scandinavia, you’ll find a lot more balancing of the extremity of the free market. They are more likely to spend money on, for instance, a well-balanced, well-funded architectural competition for a site, whereas in the UK we tend not to, or if we do they aren't well-funded so everyone is pitching against each other for very little money.

I’m a bit of a nostalgist for city planning, and in America you can go to some cities like Portland, Oregon, where they dabbled with spectacle in the mid-70s/80s, but actually as part of a long 30-40 year plan to improve conditions in the city. Where the citizens of a place have been more involved in the planning and maintenance of their city, there tends to be less spectacle.

| DBW: You discuss the trade-offs between local government and property developers over Section 106 obligations, and how consultants are now employed to find loopholes in the viability of development schemes. Do you think government should, or could, do something to try and address this worrying trend? |

TD:

I am a great advocate for bolstering and reforming the planning system in this country. We have a peculiar situation where we had only a very few years, in the post-war period, of heroic planning and then it started gradually being dismantled from the 1950s on.

That’s not to say that this planning culture was perfect at all - it was very top-down as was the culture at the time. But we have a situation now where, on the one hand we have leftovers which are hyper-regulated such as the Green Belt, and most other areas where things have been loosened to such a laughable degree that you get developers that do everything they can to get out of their Section 106 obligations.

There’s been talk of planning reform for decades but no one has been strong enough to actually do it.

| DBW: You point to the elevation of ‘starchitects’ as being a firm feature of this age of spectacle. If you look at the list of commonly-acknowledged starchitects, one thing they almost all have in common is that they are rather old! Is our veneration of them and the new ‘spectacles’ they produce a reflection of the same kind of nostalgia that you can see cross-culturally, such as in popular music, with ‘heritage acts’ like the Rolling Stones, The Who, et al, still proving such a box office draw? |

TD:

We’ve had starchitects before but never quite in such the same number or their status never quite communicated as strongly as now. It’s a phenomenon that comes off the back of the revolutions in the media over the last 20 years. The internet has obviously changed the nature and speed at which we are able to communicate images, so we see a similar condition with celebrity and many other fields.

The starchitects I talk about in the book are of a certain generation that emerged in the 1970s, but there are plenty of younger people now who may not be household names but are certainly on their way, like Bjarke Engels, David Adjaye. Architecture is a long game, it takes a long time to establish one’s name.

| DBW: You conclude the book on a fairly downbeat note, viewing the continuation of the spectacle as inevitable. Are there no signs that this is a trend that has peaked and will now decline, or do you see it continuing as long as the political economies keep on compelling it? |

TD:

It is attached to a certain economic condition, neoliberalism, globalisation and the free market. Obviously, all of that is currently under review, there are lots of cracks, but there’s no sign of it disappearing. I don’t see any viable replacement, but ‘what’s next’ is often right under our noses and we can’t see it yet.

The interest in collaboration and cooperation, certainly among a younger generation of architects and designers, an interest in high-tech as well as the democratic possibilities, is encouraging. Technology often comes accompanied by claims of ‘freeing us all’, we can be cynical about those, but sometimes it works and does liberate us in some way.

In terms of the revolutions taking place at the moment in the design platforms and production of stuff – 3D printers, drones building buildings – these will have an impact on the industry and there are certainly democratic and emancipatory possibilities in all of those. So I am quite optimistic, but I think architecture can only reflect the conditions under which it occurs, and at the moment we are still in a state of advanced free market capitalism and the condition of spectacle has come about as a result of that.

| DBW: The architecture of spectacle is, as you say, a reflection of late-20th century neoliberal capitalism. Could the emergent technologies such as smart cities and the internet of things that are changing society lend the way for a new kind of 21st century ‘digital architecture’? |

TD:

Certainly, but they could also have negative as well as emancipatory impacts, such as data surveillance. The jury is out at the moment, but the possibility is certainly there. At the end of the day, it all comes down to ownership and control of our environment - what involvement do we have?

If there’s one key message I wanted the book to get across it is that we all become very passive spectators of our cities rather than being involved in their creation. There’s the possibility for us to be more brave and bold in terms of involvement.

| DBW: Documentaries you’ve made include ‘The Secret Life of Buildings’. How do you think architecture and design should adapt, in particular the training of those disciplines, to accommodate the research evidence that has been amassed in recent years about the impacts of buildings on occupants’ health and wellbeing? |

TD:

Don’t get me going on that! I do some teaching at university, and I think education of architects has been undergoing such fundamental reform.

At the moment my observation is that architects are taught far too much design and too little science, psychology, sociology. 10% of their time is spent learning history and theory at undergraduate level, 90% seems to go on design.

Personally, I think all undergraduate architecture students should be taught politics, economics and sociology as well as engineering. Other disciplines that study the psychology or the neuroscience of spaces and their impacts on people, only a fraction of their work gets through to practicing architects, which I think is terrible.

| DBW: There is a lot of talk at the moment about microhousing as a means of tackling the plight of Generation Rent. What do you think of the idea, and should high-profile architects/designers be focused on tackling these pressing issues, as with Brutalism in the 50s/60s, rather than focusing on new and more spectacular icons of wealth? |

TD:

Absolutely, yes. Certainly there are younger architects who are - Assemble who won the Turner prize a few years ago have become figureheads-of-sorts. Also people like Peter Barber who’s been quietly designing low-cost housing and housing for the homeless for 20-25 years, and doing so in a beautiful manner.

But we are beginning to see some efforts and interest again in modular housing and prefabrication, which I see as key to how we’re going to solve the housing crisis. People like Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (RSHP) have become involved, and George Clarke of all people spearheading modular housing up in Tyneside with Urban Splash.

At the end of the day, it comes down to power and control, and we’re not going to solve the housing crisis until there’s a change in political will, which in itself is tied up in all sorts of things, such as the fact that most people who vote tend to be over 40 or 50 who probably don’t want their house value to go down. It’s their children who are instead stuck with the problem.

| DBW: What was your reaction to Sadiq Khan’s effective scrapping of the Garden Bridge |

TD:

With my ‘critic’s head’ on, I thought it was fantastic. I don’t think it was a good design scheme, I don’t think it was in the right place, and I had huge problems, as many did, with the way it was procured and grafted onto a community. It did smack of being very much a vanity project.

With my ‘historian’s head’ on, I’m also pleased that it’s gone because it will now only exist as a ‘what might have been’. It’s fascinating to me that it’s a scheme that used digital media, virtual reality, and such like, as a way of trying to drum up interest and spread its image with great provenance to potential sponsors. Future historians will enjoy exploring all of that, as it will be a ghost project from now on.

| DBW: Do you have a favourite building? |

TD:

I have many, but I think Durham Cathedral [see image below] is probably my favourite. I’m a great lover of Romanesque architecture, purely for its aesthetics, I love fluidity and ‘the massive’.

For the same reasons I love Brutalism. One of my favourite places in London is the National Theatre.

| DBW: If you could demolish one building tomorrow, what would it be? |

TD:

Just get me going…! Narrowing it down, I really dislike Drake Circus in Plymouth, but I would go for Beetham Tower in Manchester [see image below].

It’s a building that takes so much from the city and gives so little. For me it’s an incredibly ugly building; I have no problem with skyscrapers at all as long as they are properly planned and give something to the city as well.

So many city skyscrapers that have residential populations, the properties are sold based on the views looking out from the luxury apartments, but there should be a tax on them because they have to be viewed by everyone else.

| DBW: In terms of housing and planning, is there one policy that you would put in the next government’s manifesto? |

TD:

Proper devolution of planning powers to local communities - proper localism.

Obviously that comes with a lot of details necessary, but I don't mean the kind of localism that David Cameron tried to bring in, I mean proper devolution and involvement of people at a neighbourhood level.

| DBW: Do you know what the focus of your next book will be? |

TD:

I'm writing the proposal at the moment. It will be on the home. I'm hoping it will be a memoir of my life seen through the home, as a way of looking at how Britain's relationship with housing has changed over the last 40-50 years.

To purchase 'The Age of Spectacle' see here.

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Interview with Kevin McCloud 2017.

- Interview with Kevin McCloud 2018.

- Last Futures: Nature, Technology and the End of Architecture.

- Living in the hyperreal post-modern city.

- Owen Hatherley interview.

- Peter Barber - interview.

- Peter Barber lecture.

- Planning obligation.

- The Architecture of Neoliberalism.

- Will Self interview.

Featured articles and news

How can digital twins boost profitability within construction?

A brief description of a smart construction dashboard, collecting as-built data, as a s site changes forming an accurate digital twin.

Unlocking surplus public defence land and more to speed up the delivery of housing.

The Planning and Infrastructure bill oulined

With reactions from IHBC and others on its potential impacts.

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

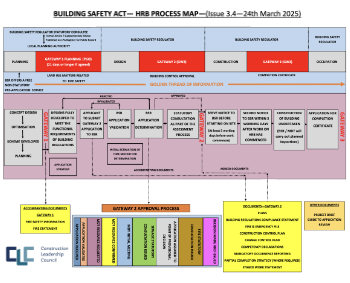

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Architects Academy at an insulation manufacturing facility

Programme of technical engagement for aspiring designers.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.

The restoration of the novelist’s birthplace in Eastwood.

Life Critical Fire Safety External Wall System LCFS EWS

Breaking down what is meant by this now often used term.

PAC report on the Remediation of Dangerous Cladding

Recommendations on workforce, transparency, support, insurance, funding, fraud and mismanagement.

New towns, expanded settlements and housing delivery

Modular inquiry asks if new towns and expanded settlements are an effective means of delivering housing.

Building Engineering Business Survey Q1 2025

Survey shows growth remains flat as skill shortages and volatile pricing persist.